The 2012 study A Single Bout of Exercise Improves Motor Memory published by scientists in Copenhagen found that exercise impacts the development and consolidation of physical memories. What particularly caught my eye were the findings that:

“A single bout of intense exercise performed immediately before or after practicing a motor task was sufficient to improve motor skill learning through a better long-term retention of the skill.”

“The positive effects of acute exercise on motor memory are maximized when exercise is performed immediately after practice, during the early stages of memory consolidation.”

These discoveries gave me pause. What if I were to incorporate acute exercise–that is, exercise of sudden onset and short duration–into the teaching of my 8-Steps posture techniques? By so doing might I improve learners’ long-term retention of individual components of each posture lesson and–ultimately–speed up and perpetuate their recovery of primal posture?

Because the study authors note that the effects of acute exercise might have important practical implications in rehabilitation, as well as in sports, and because helping people in pain rehabilitate primal posture is my life’s work, the notion of exercising to reinforce primal posture is a topic worth exploring.

What is motor memory?

Often referred to as “muscle memory,” motor memory, or motor learning, underlies the expression: “Once you learn how to ride a bike, you never forget.”

Motor memory is what’s involved as my fingers rapidly type this sentence on my laptop keyboard and what my husband unconsciously employs when he sits down at the piano and plays Scott Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag.” Of course “muscle memory” has nothing to do with muscles actually creating and storing memories of how to type or play keyboards. Instead, muscle memory is a sort of procedural memory that consolidates specific motor tasks into memory via repetition and files them away for future reference. It’s the form of memory that enables a middle-aged woman who hasn’t ridden a bicycle in decades, to climb aboard, wobble for just a moment, and then confidently pedal away.

The study

Background

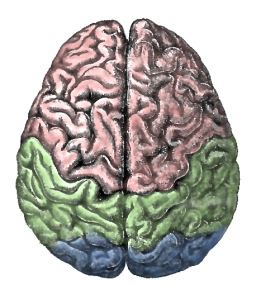

It’s well accepted that physical activity positively impacts cognition and brain function, and that aerobic exercise promotes adaptations in the human brain, among them: an increase in brain activation, blood flow, connectivity, as well as brain volume in the hippocampus, the part of the brain involved with spacial navigation and the consolidation of information from both short- and long-term memory. Until now, only a few studies focused on the effects of acute exercise on specific types of memory, and no studies investigated the long-term effects of acute exercise on motor memory consolidation and motor skill learning.

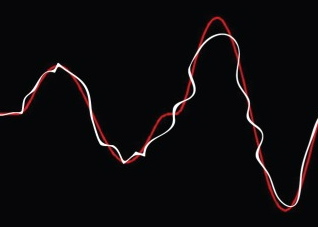

In the Copenhagen study, the men who exercised after practicing the motor skill showed improved long-term retention of the computer motor skill

Study design

- Can an intense bout of cycling optimize the acquisition and retention of a motor skill?

- Does the timing of the exercise in relation to the practice of the motor skill influence motor memory and skill learning?

Results

- Whether the men vigorously cycled before or after practice didn’t significantly impact the rate of skill acquisition.

- Regardless of when they exercised, the men who cycled showed a better long-term retention of the computer motor skill, compared to the group that did not exercise.

- The group that exercised after practicing the motor skill showed better long-term retention than the group that exercised before practicing the motor skill.

What’s the ‘takeaway’?

The timing of the exercise is important. To maximize long-term retention of motor memory, acute exercise must be done right after the memory is learned. The researchers conjecture that short bursts of intense exercise before practicing the motor skill may leave the brain overstimulated, making it less able to zero in on and access new memories. Note that the improvement doesn’t show up in the first hour, but rather when tested 24 hours or 7 days later, perhaps because after just one hour the memory is still being encoded and moving from short- to long-term storage.

Eager to explore how these study results might be applied to the teaching of Gokhale Method posture techniques, I invite you to participate in a simple, not quite rigorous experiment to test the notion that by exercising briefly and intensely after repeatedly practicing a single movement, you can cement this motor memory and better retain it over the long term. And I propose that we center our visuomotor-memory practice on a neck stretching and strengthening technique–neck-shearing (or head-gliding) from side to side.

Head gliding–a forgotten primal skill

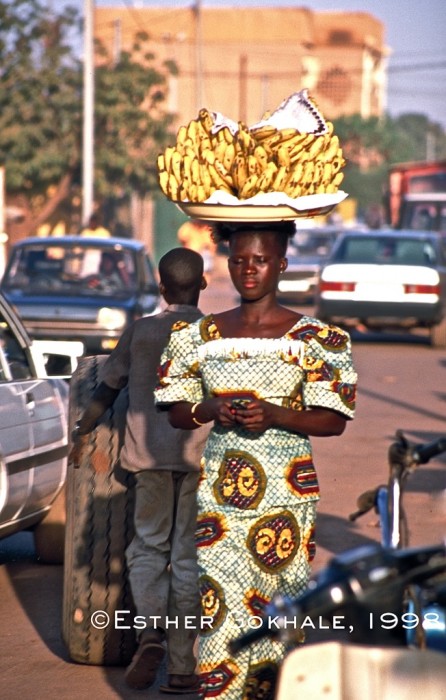

Although we all share a fine blueprint for physical well-being, it takes cultural support and repeated visual cueing, especially in the formative years, to pass body wisdom from one generation to the next. Unfortunately, many in 21st-century industrial society have lost touch with the sort of kinesthetic traditions our ancestors performed for thousands of years. One of these losses is the primal ability to balance substantial weights on our heads.

While most of us are not prepared to transport a load of bananas atop our heads, we can practice and learn to stretch and strengthen our neck muscles, without stressing the cervical spine.

Take a look:

How to head glide

The best and most natural way to practice this visuomotor skill is to:

- Sit or stand before a mirror.

- With your palms facing in, hold each hand several inches from the side of each ear.

- Keeping your body still, slide your head from side to side, aiming to touch each ear to the corresponding hand.

- To ensure that you are translating this motor task horizontally and not moving your body, keep looking at yourself in the mirror.

- Practice this head-gliding movement from side to side, again and again, until you think you’ve got it.

- Then, on a scale of 0 to 10, self-evaluate how successful you were in head-gliding.

- Jot down this number for future reference.

Speeding up learning headgliding TeleSeminars

To very loosely test whether engaging in a short bout of vigorous exercise after practicing a visuomotor skill will enhance long-term retention of this skill–I invite you to join me for two 30-minute online meetings:

Saturday, August 10th, 10:30am PT

Sunday, August 11th, 10:30am PT

To register, click here.

As a preview, please view the above 2-minute video clip at least once.

While the protocol we’ll follow is not rigorously scientific, it will be fun and–with practice–may leave you with a new and useful skill. Beyond all this, our experiment may lead to interesting results you can apply to other motor skills you’d like to learn and retain.

We look forward to seeing you!

What would Copenhagen researchers say about this?

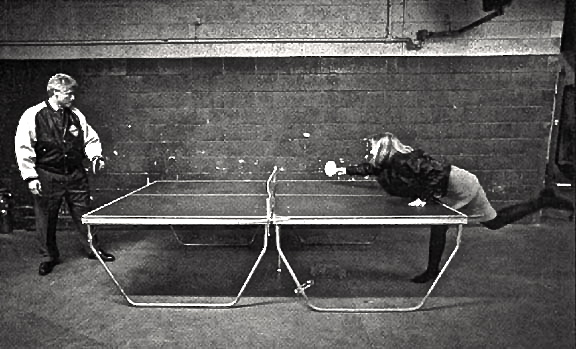

Finally, just for fun: Is the motor memory being reinforced by vigorous hammering before and after “the pause that refreshes” a memory of how to grasp and raise a glass? (The video runs for just 39 seconds.)

Photo and Video Credits:

Left-Right Brain, Creative Commons

Child on a Bicycle, Jacob and Marlies, Wikimedia Commons

Bike Rider, Josh Bluntschli, Wikimedia Commons

Stationary Bike Riding, Wikimedia Commons

Visuomotor Tracking Task Graphic, M Roig et al. PLoS One. 2012; 7(9): e44594

Burkina Faso Woman Carrying Bananas, Esther Gokhale

Neck Shearing/Head Gliding Video, Gokhale Method Institute

Blacksmiths, 1893, Thomas Edison, YouTube uploaded by cpenter